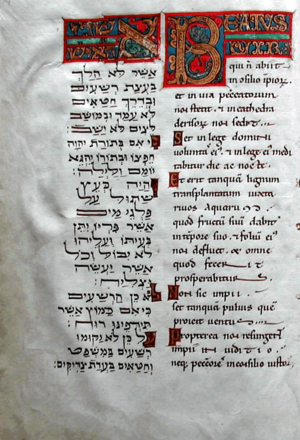

| The Psalms in Hebrew and Latin. Manuscript on parchment, 12th century. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

First, understand that I do appreciate that the Psalms are sacred poetry. I've read various books by Thomas Merton including three with a heavy emphasis on the Psalms (Contemplative Prayer, Praying the Psalms, Bread in the Wilderness), I've read Psalms: A Spiritual Commentary by Basil Pennington, I've read Psalms: The Prayer Book of the Bible by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, I've read The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris, Prayers from the Darkness: The Difficult Psalms by Lyn Fraser, and so on.

Second, I read these books while studying as a novice oblate with a Benedictine community and wrote reports examining and reflecting on them and the discussing my thoughts and reactions with a Benedictine to further delve into meaning and response. This was not casual reading.

Third, prior to and during the novitiate I regularly performed the Daily Office and chose a schedule for the readings which completed the Psalter once per month. I did this for over a year and a half. I am familiar with the Psalms themselves.

My relationship to the Psalms then isn't based on a casual acquaintance, nor is it based on a fundamentalist or literalist mindset. I realize that there are cultural and historical differences with the writers of the Psalms and today's readers of these ancient poems, and that poems are not to be read as prescriptive theology. Yet I am still not fond of them and don't connect with them.

And now I'm going to suggest what value they can possess for anyone on a spiritual path, whether or not they identify with the Bible or the Abrahamic religions.

The Traditional Christian View of the Psalter

The traditional and conventional view of the Christian Church concerning the Psalms is that they are supposed to be a poetic incarnation of Christ manifest through the hearts and pens of their authors. The Psalter is supposed to reflect the heart of the Church, it is Christ's prayer to the Father bringing out petitions before the throne of God.

The Psalms alternate between praise for God as creator, sustainer, defender, and source of justice on the one hand and the cries of the fearful and offended with pleading, lamenting, complaining, bargaining, and cursing on the other. The latter themes, especially when found in the imprecatory Psalms, revolve around cycles of arrogance, fear, guilt, resentment, and retribution.

This perspective is very black and white and calls for taking sides, with death and destruction called down upon all who are deemed to be enemies. Peace and mercy is praised, especially when it is granted to the faithful, but even this comes at the cost of annihilating the Other. The Psalms are highly nationalistic and jingiostic, and make no distinction between the sin and the sinner.

Sister Joan Chittister of the Benedictine Sisters of Erie, who has a very mature and contemplative perspective free of fundamentalism or superficiality, writes many interesting things about Benedictine life and freely draws upon Judaism, Islam, Taoism, and Buddhism in her work. I wondered if she might give some insight into how to appreciate such themes of divisiveness and judgment, but even she writes about the comfort of the Psalms and their promises of God's power to punish the wicked and lift up the despised.

This is where I part from mainstream Christianity. Nothing in my experience or knowledge of the world allows me to believe that the kind of blessings and curses from an omnipotent deity as described in the Psalms and similar part of the Bible are real, and nothing in my ethical system and moral understanding would accept such a deity. Any meaning or value they might have to me must lie elsewhere. (Yes, some views see the talk of violence and judgment as indicating shaming and reproving others or even fighting ones personal demons, but these are not widely accepted contemporary views.)

Of course, the Psalms existed long before Christianity arose and separated from what has become rabbinical Judaism, and I cannot say to what degree various forms of Judaism would see the Psalms as comforting promises of God's justice and mercy in terms of sending out supernatural blessings and curses, but I suspect this is not unfamiliar to the Jewish traditions either.

Beyond the Traditional Christian View

There are many ways to appreciate the Psalms, and of the authors previously mentioned, Kathleen Norris comes closest to a perspective I can appreciate (with Bonhoeffer the furthest). She doesn't seem constrained to fit the Psalms into such a formal intellectual and theological framework, allowing the poems to provoke their own messy theology of the heart. And Lyn Fraser makes a compelling case that the Psalms echo our fear, pain, and sense of betrayal, hopelessness, and powerlessness, giving voice to that which we might otherwise be ashamed or embarrassed to admit in ourselves in times of crisis.

Putting aside the need some have to try to make the Psalms prophetic about the coming of Jesus Christ or the final judgment, even the more theologically inclined authors I've referenced tend to emphasize the importance of the symbolic as well as the felt sense of the Psalter. It is unlikely that the authors of the Psalms really believed that no misfortune would ever come to those who were faithful to God, as they only had to look around to see bad things happening to good people. And references to lions, serpents, bulls, and dogs are somewhat transparent in seeming to refer to haughty pride, being too clever or cleverly deceitful, boastful vanity, and a rabid pack mentality.

At times such qualities may refer to actual external foes, and at times to ones own shortcomings. The poetic vagueness of the Psalms allows this slippery quality that permits a different experience of a particular Psalms on different readings. The themes are common to the highs and lows of human joys and miseries, and even the depths of its depravity, making them both universal and a window into the soul. Hence their continued relevance from age to age even as the religion and external theology surrounding them shifts and twists over time.

The Psalms as Mirror and Inner Voice

Christianity and Buddhism both emphasize finding the divine, either as God or nirvana, in the midst of what seems to be corrupt, filthy, broken, or useless. The mustard seed (a weed) rather than a mighty cedar, leavened rather the unleavened bread, the publican rather than the pharisee, the lotus blooming in the mud, the bits of rubble turned to gold. But as I've noted before, while some may talk about being one with all things, but they would rather be one with the butterfly or the rainbow rather than the landfill.

If we really mean it, though, then we have to examine and accept more than just the parts we think are pretty or uplifting in an obvious way, including what we might consider faults or flaws. If you want to talk about finding the Kingdom of Heaven in the leaven or seeking the lotus blooming in the muck, then you have to go through, not around, these things. The divine is not waiting there like the marble in the oatmeal, so that once found the oatmeal can be discarded. There's no cosmic firehouse to clean you off after you are done. There is no quick and easy shortcut around the process.

If you are looking to find a light in the depths of the darkness, you can't deny or turn away from the darkness. As the existential philosopher Albert Camus wrote, "In the depths of winter I finally learned there was in me an invincible summer."

There is a big temptation among spiritual seekers to think of themselves as humble and equitable when they are harboring deep-seeded egoism that subtly manifests as being "holier (or bodhier) than thou." It is easy to not recognize that the things which offend us in others may reflect our own disposition. I like to think that I don't want judgment and destruction on "sinners", that I want us all to be one harmonious community of humankind that forgives and works for the betterment of all. I like to think that the high-minded values of cooperation and compassion for everyone.

Then I remember I sometimes harbor my own wishes for people who cause harm to others through carelessness, self-absorption, or intentional cruelty to be corrected, to suffer, and to grow up and become more responsible and thoughtful as a result. I meditate on these and other triggers for my anger and frustration. Because my anger is often mild and short-lived, often not rising beyond a brief flash of annoyance that doesn't even break the surface of my expressions, it is not hard to sell myself the fiction of my calm equanimity. (Those who live with me have a different view of course.)

The Psalms, as has been suggested many times, can act like a mirror and reveal much about us by our reactions to them. They give a voice to the things that we try to silence, rudely making their reality known to our conscious minds. But denial and repression never work, and can only cause such passions, either defeatist, triumphalist, or despondent, to continue to linger and lurk and make facing our shadows a frightening or disheartening project. What is there is no light to be found, on more shadow?

I don't see the Psalms as promises or fortune-telling prophecies to be celebrated. That kind of perspective doesn't work for me. They offer a different kind of prophecy, a more psychological and spiritual message, upon which the reader (or chanter, or singer) must meditate. Do I want solidarity with all of humanity, including what I judge to be their flaws and weaknesses? Do I want to feel their pain in a non-dual unity of experience as one of them? To know their elation, disappointment, fear, despondency, and rage? To see myself as tarnished, blemished, and impure? To realize that the contents of their lives are also the contents of my own? Or do I want to keep up the illusion of being much nicer and kinder and caring than I sometimes feel or act?

And then I start to see how people could read the Christ imagery into this. Not the complex theology of official Christendom, but the idea of facing our full humanity and embracing it all. Taking that part of our consciousness we connect with virtue and perfection and our preferred self image and opening the windows to let the self-righteous odor out. And for the part already in the gloom of self-reproach and isolation, connecting back to a sense of connection and worth. The different parts reunited. Whole--which shares the same root a the word holy.

That reminds me of something Merton had written about the Psalms, and about God finding herself in us. It reinforces the image of Jesus becoming the Christ in an inclusive way, as a part realizing its connection to the whole and that the whole was already found in the part. The image of our petitions being laid before God also shifts, not as messages to an external being hovering over the universe but as a recognition of our deepest and truest selves. Not as some fixed essential kernels of self-hood but as part of a larger flow and web of conscious awareness between people that gives birth to our identities as it connects us to each other and shapes us by our perceptions and choices.

None of this imagery requires a belief in what people commonly think of when they think of "God". This is the ancient God, not the tribal deities or the philosophers metaphysical construction. It is the God expressed through irrational exuberance and hyperbole but which can never be reduced to descriptions or concepts. Bringing something before this God is through the Psalms an act of sacrifice, placing the doubts, fears, joys, judgements, grudges, resentments, hopes, and the rest into a crucible to see what remains. What is left when the smoke clears?

Post-Script

This approach provides a different context for blessing and curses as well, and many other things that have become stale and lost much of their meaning over the centuries as other aspects of culture, knowledge, and the nature of lived experience has changed. Students of more advanced teachings of the Dharma may recognize some of their own teachings and practices in the meditation on the Psalms as well. If anyone outside of the Abrahamic religions uses the Psalms in some way, it would be great to hear about your experiences.

On one level, I suppose I have a bit of a better understanding of the Psalms and their appeal to many people, but on another, I cannot say I am much fonder of them. Perhaps it is because of associations with other ideas and experiences associated with certain forms of Christianity which advocate intolerance and divinely sanctioned violence and torture or which are associated with literalism and fundamentalist interpretations of the Bible such as an anthropomorphic super-deity as a "God" who is drowning in theodicy, but the Psalms are still not my cup of tea. One should not mistake my analysis of why the may be helpful or meaningful with the assumption that I actually feel that way about them or that they have such an effect on me.

Ran across this over lunch, a little more on how the Psalms are perceived and used.

ReplyDelete