Even as they rail against the so-called gay agenda and wring their hands over what they perceive to be the legitimization of immorality, homosexuality remains a source of sin of which for which many who identify as Christians are guilty and for which they have yet to repent. But the gay community and its allies may yet set them free.

I say this for good reason, but there are some reasons that I do not claim. I don't claim to speak for anyone other than myself. Nor do I have any desire to pass judgment over any particular person or set myself up an official arbiter of religious righteousness or holiness, whether for Christianity or any other tradition.

But I do choose to emply the language some Christians use in passing judgment and condemning others for their sexual orientation (and we can expand that to their hangups over gender identity as well) in describing some observations about their perspective and behavior that I find objectionable.

A few words on sin

I find it interesting that sin and salvation can be understood in terms of spaciousness. The Jewish conception of salvation has a direct connection to the imagery of spaciousness, of being in a broad and fruitful place. This imagery can be taken in many ways, including phenomenologically, literally, metaphorically, imaginally, practically, and so on. Similarly, sin is connected to being confined, of being in a pit, or bound in chains, or in a desolate place.

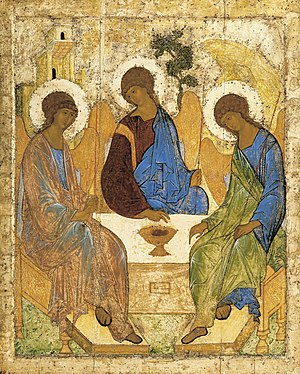

As an offshoot of one of the first century sects of Judaism, Christianity has appropriated much of the imagery of its cultural forebears, at times keeping its original sense and at times modifying it. Dante Alighieri used this same imagery of constriction, for example, for depicting Hell as a place that gradually becomes narrower and more sparsely populated until it reaches Satan stuck in a small, dark, isolated space at the bottom.

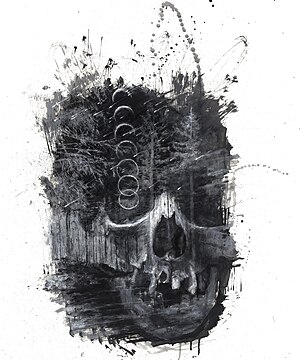

Taking in this imagery, it suggests that the more deeply one becomes lost in such limiting and stale space, the more one descends into a barren, joyless, and fruitless existence. Shallow diversions and intense emotional distractions may temporarily seem to liven up this space, but their effects wear off more quickly after each use. A sense of hollowness and a deep malaise lurks when the noise stops. When silence is heard once more in the heart and mind.

The more time one spends in such a space, the more it changes a person. While the effects may not be perfectly consistent or universal, they involve a deep insecurity and sense of being unfulfilled. How these effects are expressed also varies. Some respond to this by denial, oddly enough by trying to fill their lives with noise that gives at least the appearance if not the sensation of being confident and successful. This becomes transmuted into arrogance and greed.

Other coveted virtues yield similar results, with condescension and cheapness masquerading as charity, manipulation, coercion, and gossip as concern, and so on. Unable to experience or express the genuine article, the counterfeits are tainted or corrupted. This perversion isn't necessarily intentional, and may in fact be the result of better intentions. Outwardly things may appear pleasant if not a little artificial or overdone.

Based on my own experiences and the reported experiences of others, this kind of sugar coated hypocrisy has become a stereotype of the evangelical fundamentalist Christian. They are by no means exclusive in having members that fit this mold. It does seem to be related, though, to seeking the kind of noise that covers the unease and gives the desired appearance and sense of self. A kind of noise that betrays a sense of not knowing or being comfortable with what it is they claim to possess.

This noise is manifest as an externalizing desire that transforms that hidden need to possess, to control, what they claim to already have by turning it into concrete expressions. Expressions based on loose perceptions of something they understand only in words and gestures. Thus "Jesus", "Christ", "The Cross", "God", "Salvation", "Heaven", and others are sold as books, music, decorations, and knick-knacks in circular, self-referential theology and diluted liturgy.

Some may end up resembling this stereotype based on imitation and inherited cultural patterns, so the underlying dynamics described aren't meant to reflect everyone who in someway resemble this stereotype. Nor is this stereotype the only outcome of those who find themselves in such a stifling, suffocating space. Rather it seems to be an outcome for those who are trying to convince themselves and others that they really do have the "fruits of the Spirit" (love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control) when they lack sufficient inner spaciousness, springs, and light to bear them to the degree that they wish to present.

For those who are unfamiliar with or who have an aversion to religious language, as well as for those who recognize it but want to see how it works into the observation I started with, allow me to briefly unpack that imagery a little as I show why this relates to fundamentalist attitudes toward issues such as sexuality and gender identification.